The road ahead for climate transition plans

The quality and uptake of net zero strategies is currently low, but regulators are wading in to make companies step up.

Only 81 companies have an adequate climate transition plan, according to CDP.

Out of the 18,600 firms that reported via the environmental data platform in 2022, just 4,000 disclosed a plan at all. Of those, less than 1% disclosed against the 21 indicators CDP said “denote a credible climate transition plan”.

That number is set to climb, however, as legislators around the world begin mandating companies to explain how they will align their businesses with the transition to net zero.

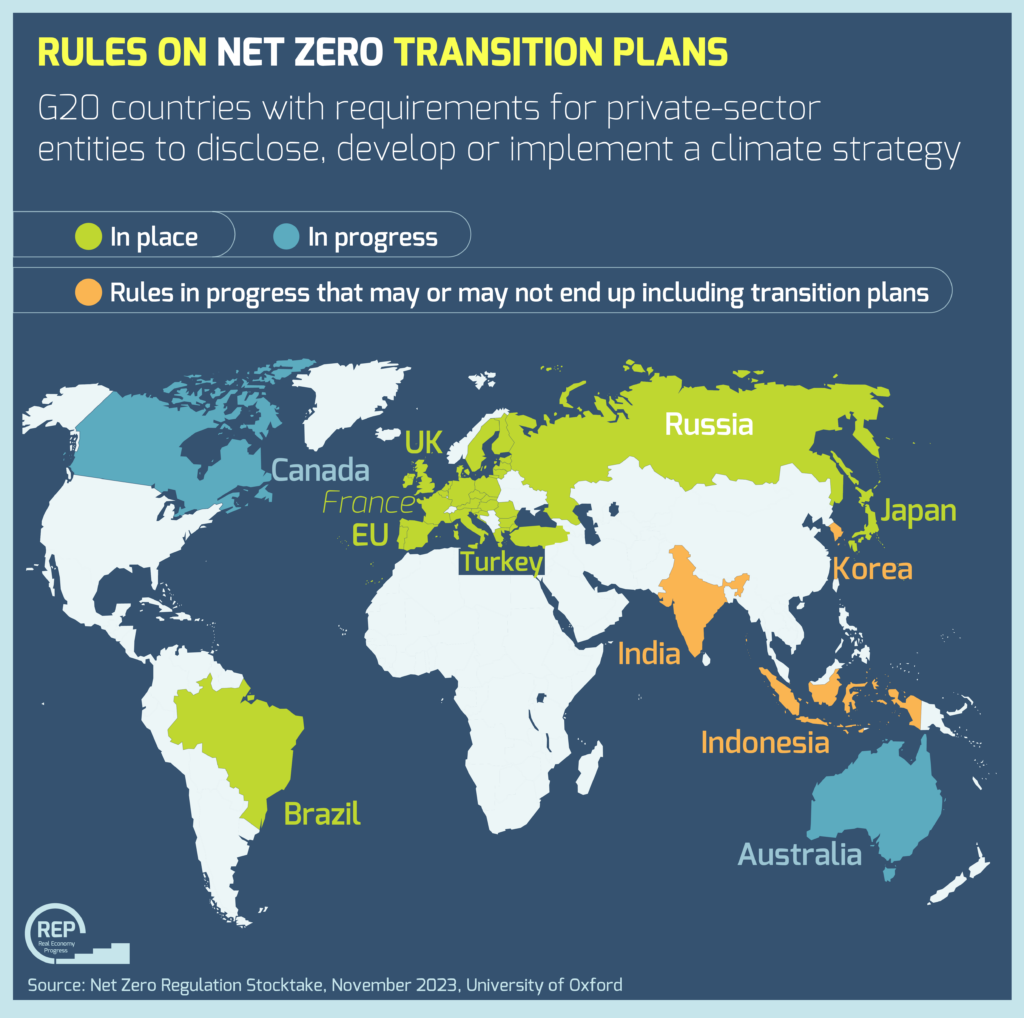

Researchers at the University of Oxford have identified 13 countries that already have relevant rules in place, or are in the process of introducing them – including the UK, Canada, Brazil, Australia and France.

Lucilla Dias, the researcher leading the Oxford Net Zero initiative, says that much of the current legislation is based on the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which were updated in 2021 to include expectations on transition strategies for the first time.

“The logic is that first you identify your [climate-related] risks and opportunities, and then you add a layer of disclosure around what you plan to do about them: that second part is the transition plan,” Dias explains.

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has TCFD rules in place already, but is due to strengthen the requirements to incorporate guidelines developed by the UK’s Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT).

Those guidelines are also beginning to be considered as best-practice by rule-makers in other jurisdictions, and CDP is expected to align its disclosure requirements with them by 2025. For more, see this article.

Going beyond entity-level decarbonisation

“TPT has introduced the idea that companies’ plans need to address their role in supporting the whole-of-economy transition, rather than simply focusing on entity-level decarbonisation,” says Mark Manning, a Taskforce member and former sustainable finance policy advisor at the FCA.

The guidance calls for firms to explain how they will engage with policymakers, peers and players in their value chain, for example.

Manning acknowledges that these expectations raise some important legal points for companies.

“A question that’s come up a lot is: if you’re taking a truly systemic approach to this, are you going beyond your duties as a director?”

The TPT guidelines are clear in framing these broader efforts as a way of managing systemic risk in order to safeguard value for shareholders, making them consistent with the conventional understanding of directors’ duties, Manning points out, adding that “the two objectives will become even more clearly aligned as governments develop national net-zero roadmaps and encourage similar strategies from actors across the whole economy”.

From transparency to behavioural change

For now though, most of the rules don’t actually require the development of strategies.

“The regulation is coming largely from financial regulators, who are often only able to mandate disclosure,” notes Dias.

The FCA’s rules, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and Australia’s upcoming measures are among those that simply require entities to publish a climate transition plan if they have one.

Dias believes it’s up to other legislators to go beyond transparency, and begin to force behavioural change.

Switzerland has moved a step further in this direction by introducing a legal requirement for companies to develop net zero plans, and then disclose them. If sufficient, they could enable businesses to gain access to subsidies and other government support in the future.

But last month’s legal agreement on the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D) marked a major step-change in this type of rulemaking.

Details of the law are still being negotiated, but it includes provisions for companies and financial institutions to develop and pursue time-bound decarbonisation plans in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“I don’t think many organisations appreciate that CS3D isn’t just a requirement to develop a transition plan, it’s a requirement to implement it,” says Tracey Groves, head of ESG and sustainability at law firm DWF.

“That means a company will need a plan that’s aligned with its overall business strategy, but it also needs to be able to execute on it,” she adds. “The vast majority of companies are nowhere near getting their heads around the implications of that.”

According to CS3D, there are seven core elements a transition plan should cover, ranging from a firm’s exposure to climate-related risks and opportunities; its impact on climate change and relevant stakeholders; five-yearly decarbonisation targets and how it could achieve them, including financing plans; and its governance strategy.

Given the scale of the task, and the 2027 deadline for the first batch of companies (those with more than 500 employees and €150m in turnover), Groves recommends that companies start doing at least the “bare minimum” across all seven, instead of waiting for more details and best practice to emerge.

“If you think about the time it takes to implement some of these things, companies can’t afford to wait around for more clarity,” she says.

The final text for CS3D is expected to be voted through by Council and Parliament by April. The European Commission should have developed additional guidance within two years.

Wider knock-on-effects

Even firms that aren’t covered directly by all these emerging requirements could find themselves on the receiving end of requests for climate plans.

Unlisted companies, for example, remain largely out of scope of the requirements (apart from in the UK, where large LLPs are covered), but many of their lenders and investors will have to comply.

“That’s good because it will require them to know the transition plans of their clients and portfolio companies,” says Manning. “So the demand will cascade downwards, encouraging accelerated action without the need for lots more regulation.”