What does SBTi’s cull say about the state of corporate climate targets?

Greenwashing, practical challenges or different takes on climate science: Why did more than 200 firms have their net zero targets dropped?

This time last week, Real Economy Progress broke the news that the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) had removed the net-zero commitments of more than 200 companies, after they missed the deadline to set eligible targets.

Market reaction to the story came thick and fast. Many observers praised SBTi for showing its teeth, and booting out companies that weren’t serious about decarbonisation. Others saw the news as an indication of how much more work needs done around Scope 3 measurement. Some said it was evidence that firms shouldn’t make pledges without having first fleshed out the details.

Is it a case of mass greenwashing?

The top reason companies gave for joining the 2021 Business Ambition for 1.5°C campaign, which required them to set SBTi targets, was to “showcase their leadership”, not transform their business models.

In the same survey, nearly three quarters of respondents told SBTi they had had their expectations met.

The press campaign to promote the launch of BA1.5°C was significant. It helped secure its members thousands of namechecks in corporate sustainability reports, media articles, and statements from NGOs. Global Compact even produced pre-written social media posts to encourage CEOs to promote their firms’ pledges to the wider public.

In stark contrast, there was no press release, public announcement or social media post to draw attention to SBTi’s recent report about how companies had actually executed on the commitments; and those that failed to meet the deadline were removed from the initiative’s ‘dashboard’ without fanfare.

The UN’s webpage to promote BA1.5°C, which it describes as “a communications and advocacy campaign”, now automatically redirects to a page about the Sustainable Development Goals.

So, the PR perks of joining BA1.5°C seem to have far outweighed any potential to be named-and-shamed for not following through on the pledge.

Serious practical challenges?

But even for companies that were sincere about their commitments, there have been challenges with meeting the deadline.

The most common reason firms cited for failing to set their targets was that SBTi’s “net-zero standard had not been published” in time for them to meet their deadline.

Speaking on social media last week, Bill Baue, one of the architects of SBTi and now one of its loudest critics, accused the initiative of having “set a timeline expectation for BA1.5°C companies, then failed to deliver the materials necessary to fulfil the expectation”.

“Not that I’m arguing for letting companies off the hook, but we also shouldn’t let SBTi off the hook,” he added.

French regulator AMF recently highlighted some other practical issues that listed companies had encountered when trying to meet SBTi’s deadline, in a report about transition plans.

While some firms complained about the initiative’s apparent lack of transparency and accountability, others complained they did not get enough support to enable them to set eligible targets.

“Given the timeframe of the disclosure obligations and the number of requests, concerns are emerging around the response periods from SBTi and the risk of a ‘bottleneck’ forming,” wrote AMF, adding that one company in the industrial sector “expressed doubts about the ‘SBTi’s ability to respond promptly enough to meet the issuer’s publication obligations’.”

SBTi acknowledged this issue in its own report, noting that many companies wanted “more direct communication with target-validation staff, more flexibility on deadlines and more resources to handle enquiries and provide technical support”.

Other challenges stemmed from issues beyond SBTi’s control, such as companies dropping the ball when key members of staff left.

Are companies not aligning with the science?

Some big names – including Eurostar, Asda and Twitter – had all of their targets pulled by SBTi; but more than half the firms whose net-zero commitments were removed have retained approval for their shorter-term targets. That means their Scope 1 and 2 emissions are still tracking scientifically-credible, 1.5°C-aligned pathways, according to SBTi.

When Real Economy Progress asked Unilever why it had failed to set a full net-zero target, a spokesperson said: “We published the details of our net zero ambition in our original Climate Transition Action Plan back in 2021, where we were clear that we align to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) definition of net zero.

“The SBTi’s net zero definition is different, and was published after our plan was proposed to shareholders, and therefore it has not been possible to validate our ambition using their current methodology.”

IPCC defines net zero as balancing carbon emissions with carbon removals, but SBTI’s standard goes further – requiring entities to reduce their value chain emissions by 80-90% before they can start using removals.

Unilever has set a 2039 net-zero target, rather than a 2050 one, meaning it would need commit to drastic Scope 3 reductions over the next 15 years in order to get it validated by SBTi.

“Unilever’s priority remains reducing emissions in absolute terms this decade,” said the spokesperson. “We will seek to balance any unabated emissions within the scope of our Net Zero ambition, from 2039, with the same volume of carbon removals.”

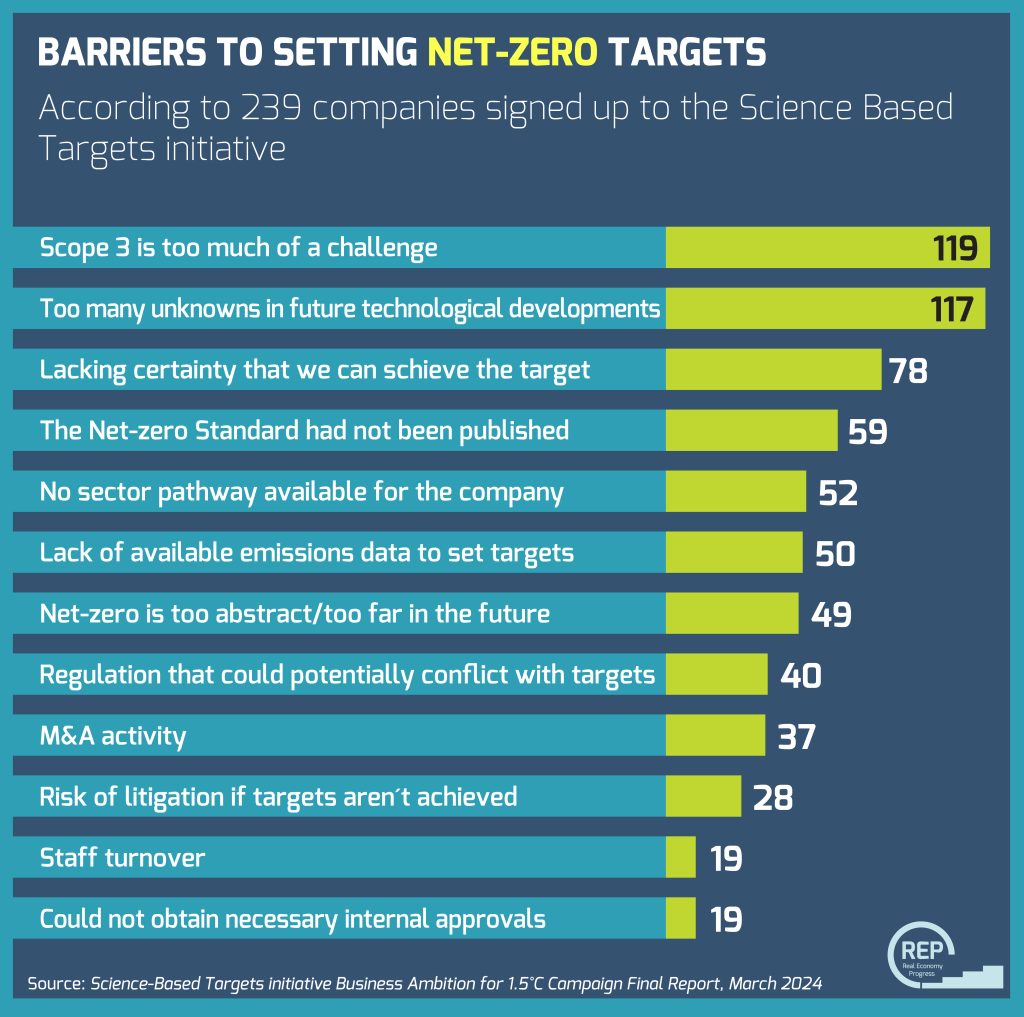

SBTi’s requirement for Scope 3 reductions was cited as the biggest obstacle for most companies trying to set net-zero targets.